Abstract

At the end of secondary general track schooling, young people experience an important transition; in Austria, they have to decide on further schooling or vocational training. Aspirations shape this transition and decisions herein. In this contribution, we explore patterns in formation, change or stability of educational and occupational aspirations. Based on an exploratory longitudinal mixed-methods approach with adolescents aged about 14 years in wave 1, we untangle the multidimensional phenomenon of (educational and occupational) aspirations. We analyze three waves of qualitative longitudinal interviews and develop a typology of young people’s educational and occupational orientation processes over time. In a statistical analysis of three waves of the panel survey data with the same age group, we compare and integrate findings on stability and change of aspirations and analyze the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on these patterns. With this mixed-methods longitudinal design, we gain an in-depth understanding of young peoples’ thoughts, ideas and worries during this transitional phase. We also learn about the resources that shape the orientation process and related patterns in time.

Zusammenfassung

Am Ende der Neuen Mittelschule erleben junge Menschen einen wichtigen Übergang: In Österreich müssen sie dann über ihren weiteren Berufs- und Bildungsweg entscheiden. Dieser Übergang wird von Aspirationen und Entscheidungen gerahmt. In diesem Beitrag untersuchen wir Muster der Entstehung, sowie Stabilität und Wandel von Berufs- und Bildungsaspirationen. Basierend auf einer explorativen, längsschnittlichen Mixed Methods Studie mit Jugendlichen im Alter von 14 Jahren in der ersten Erhebungswelle nähern wir uns dem multidimensionalen Phänomen der Berufs- und Bildungsaspirationen an. Wir analysieren drei Wellen qualitativer Panelinterviews und entwickeln eine Verlaufstypologie des Orientierungsprozesses der jungen Menschen in Bezug auf Beruf und Bildung. In statistischen Analysen von drei Wellen einer Panelbefragung der selben Altersgruppe vergleichen und integrieren wir Ergebnisse zu Stabilität und Wandel der Aspirationen und analysieren den Einfluss sozio-demographischer Aspekt auf diese Muster. Anhang dieses Mixed Methods Längsschnittdesigns erlangen wir ein tiefergehendes Verständnis für die Gedanken, Vorstellungen und Sorgen der jungen Menschen während dieses Übergangs. Außerdem lernen wir mehr darüber, welche Ressourcen den Orientierungsprozess und die damit zusammenhängenden Muster prägen.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

At the end of nine years of compulsory schooling in Austria, adolescents have to decide on whether they want to attend upper secondary schooling or to enter the labor market by starting an apprenticeship. This specific transition is an important crossroad for the future position of young people within society. Overall, transitions are not singular events and are characterized by processes of change, adjustment but also stability. In this context, we are particularly interested in processes of change (and stability) in educational and occupational aspirations from a longitudinal perspective as well as factors that shape these processes. Our aim is to understand how young people navigate the transitional phase at the end of lower secondary school.

Transitional processes are complex and multidimensional—yet core to understanding societies and social change. Therefore, in order to describe and understand them, mixed methods longitudinal research holds great potential. With the different methodological approaches, we gain complementary insights for a more nuanced understanding of dynamics behind the observed change or stability in aspirations over time. This multifaceted understanding can help us disentangle the mechanism behind the reproduction of social inequality, the interplay and development of structure and agency as well as the relevance of the social and institutional context on young peoples’ educational and occupational aspirations.

The data stem from a fully longitudinal, equal number, sequential mixed methods longitudinal interview study (Vogl 2023) with adolescents aged 14 to 17 years attending the general track of secondary school (new secondary school, ISCED-2) in Vienna, Austria, in the first wave of data collection. The analysis covers three waves of qualitative and standardized panel interviews with independent samples. The core interest lies in the formation and embeddedness of educational and occupational aspirations within participants’ lifeworlds. Initially, separate analysis intertwined with joint interpretations of qualitative and quantitative results and further data exploration leads to a circular analytical process. It turned out that the concept of aspirations (Stocké 54,53,b, a) is well suited for measuring what young people plan or aspire to do in terms of education and occupation. However, for the qualitative analysis a broader concept is required to capture a more general value system related to educational and occupational choices and aspirations: Educational and occupational orientations (Busse 2010; Hermes 2017; Winterton and Irwin 2012):

Orientations are general aims and expectations like owning one’s own business or managing people. In contrast, aspirations are more concrete and relate to a specific profession or education/degree, e.g. becoming a doctor or a mechanic, finishing university or completing vocational training (Winterton and Irwin 2012; Evans 2002; Kogler et al. 2023a). Thus, orientations are comprehensive and more closely aligned with a general value system while aspirations are more like concrete plans and often distinguished in realistic and idealistic aspirations (e.g., Wicht and Ludwig-Mayerhofer 2014; Evans 2002). Aspirations are an important part of orientations and can be operationalized and are common in standardized surveys on school-to-work-transitions. Orientations are more difficult to capture, more comprehensive and therefore easier to capture with qualitative approaches (Kogler et al. 2023a, 2022; Busse 2010; Hermes 2017). Based on this, educational and occupational decision-making processes can be understood as a product of these orientations and aspirations which in turn are shaped by an interplay of (social) structure and individual, socially embedded life histories with multiple interdependencies (Heckhausen and Buchmann 2019). We study young people’s educational and occupational orientation processes over time to explore patterns of time within this process. The contribution lies advances in the understanding the orientation process, which is of central importance for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to understand individual differences in career choices and to develop appropriate measures to support youth in the transition phase.

2 Theoretical background

Different theories try to explain the development of aspirations. Rational choice approaches address the class-specific cost-benefit analysis of educational alternatives. Social background influences educational success because class-specific resources lead to different manifestations of school performance, i.e. grades. These so-called primary effects of social background only partly explain differences in educational success between social classes. Secondary effects come into play when, despite similar school performance, different educational and occupational trajectories appear desirable (Diehl et al. 2016; Boudon 1974). Thus, school performance as well as family financial possibilities, information on options and motives play a role in the cost-benefit assessment regarding educational choices. Although approaches highlighting social differences in aspiration formation are mainly rooted in research on educational choices, they are also applicable to occupational aspirations (Wicht and Ludwig-Mayerhofer 2014).

In contrast, according to Bourdieu (1983), individual preferences are linked to the social position. Choices in the school-to-work transition are based on what a person considers to be options and follow preferences shaped by the individuals’ social environment, his or her idea of what seems achievable and desirable, and own experiences. However, not everybody has the same chance for the same outcomes—we live a life of choices but not all of us have the means to be choosers (Baumann 1998). Bourdieu also pointed out the importance of the educational system and its agents (teachers and others) in the reproduction of educational inequality (Bourdieu and Passeron 1977). Objective or structural options as well as subjectively perceived options are also called space of possibilities (Barrett 2015). The so-called objective space of possibilities is strongly influenced by social position and resources. The subjective space of possibilities refers to the thinkable, the unthinkable and the perceptions of options for one self, the desirable and undesirable, and the feasible and unfeasible (Du Bois-Reymond et al. 2001). This perception of options changes with experiences and interactions with others such as family and friends as well as teachers or instructors, and thus, it evolves over time (Kogler et al. 2023a).

The space of possibilities shapes the educational and occupational orientation processes and is sub-culturally formed. Depending on available resources, different educational and occupational trajectories appear possible or desirable. At the same time, economic, social and cultural capital is necessary to realize aspirations (Astleithner et al. 2021). For educational outcome, cultural capital is crucial (Feliciano and Lanuza 2017; Scherger and Savage 2010). Cultural capital comprises explicit and implicit knowledge, competencies and abilities that are valued in a society at a given point in time. Socialization processes are crucial for the transmission (and acquisition) of cultural capital. Thus, children in higher social classes are privileged and the educational system reinforces these inequalities (Bourdieu 1983; Willis 1977).

The family background is an important dimension of social inequality during the transitional phase: families can support their children differentially in this process (Zartler et al. 2020) and have different motives for occupational and educational preferences. Parents are a key source of information in the process of career orientation, but the resources and support they can provide depend on their social status (Dietrich and Kracke 2009). However, the effect of social background is not always direct and immediate as qualitative studies underline: The concept of orientations takes account of interactions and negotiations that standardized studies on aspirations often neglect (Busse 2010). Orientations are fundamental attitudes and values regarding education. They are part of the habitus and class specific behavior (Hermes 2017). From that perspective, educational (and occupational) orientations can be reconstructed from attitudes and behavior and transitions in the educational system are manifestations or products of orientations of children and their parents (Hermes 2017).

In sum, different theoretical and empirical approaches identify factors influencing the formation and implementation of educational and occupational orientations and aspirations and thus the reproduction of social inequality in the school-to-work transition. However, the understanding of mechanics behind and patterns of these transitional processes is limited (Nießen et al. 2022; Schels and Abraham 2021). Transitions are not always a “straight-lined” development process. Researching transitions, we are particularly interested in these patterns in time which requires a “more pluralistic and differentiated understanding of youth transitions” (Schoon and Lyons-Amos 2016, p. 19) beyond the measure of optimal vs. problematic transitions. Transitions and the process of change are shaped by individual resources, preferences and choices (Brzinsky-Fay 2014; Gaupp 2013; Jackson et al. 2012; Tikkanen et al. 2015; Walther and Plug 2006). Most importantly, transitions are processes over time and change is not all voluntary but shaped by an interplay of structure and agency, micro and macro levels of action. Furthermore, “choosing a career is not a one-off decision” (Möser 2022, p. 257). Theories like the circumscription and compromise theory (Gottfredson 1981; Gutman and Schoon 2012) describes the orientation process in stages. Aspirations are continuously adjusted as individuals form their self-concept and gain an understanding of opportunities. Occupations are first evaluated regarding their desirability in relation to the self-concepts and social acceptance (circumscription). Then accessibility is taken into account which leads to compromise and abandoning less accessible or compatible options. The processes of circumscription and compromise correspond with the differentiation between idealistic and realistic aspirations (Möser 2022).

Following these theoretical approaches and concepts, our aim is to detect patterns in the transitional phase at the end of lower secondary school and after. Our interest lays in young peoples’ perspectives, how they themselves see, tell and experience these transitions, how they frame their decisions and aspirations, the role of their social context and structural constraints they encounter. In that, we try to understand the formation and change in educational and occupational aspirations as well as the patterns in time this development takes. In a second step, we then assess the influence of sociodemographic characteristics and prior achievement on patterns of change and stability over a three-year period, starting in the last year of lower secondary education.

3 Data and methods

3.1 Pathways to the future

This research is based on longitudinal data from the project Pathways to the Future at the the University of Vienna. The main objective of the study was to foster an in-depth understanding of how young people’s opportunities in life develop during the transitional phase. In this study, we explore what these adolescents see as desirable, feasible or impossible, as well as their experiences of transitions between schools or entering the labor market with changing social environments, windows of (unexpected) opportunity, and obstacles and strategies for coping and adjusting plans. The initial qualitative and quantitative interviews were conducted when young people were about 14 years old, which corresponds to the last year of lower secondary education. Both qualitative and standardized panel interviews were conducted annually.

3.2 The Austrian educational system and school-to-work transitions

The Austrian educational system is characterised by early tracking after four years of primary school. In lower secondary school, pupils are divided into either the general track of lower secondary school (‘Neue Mittelschule’) or the lower cycle of academic secondary school (‘Gymnasium’). After four years of lower secondary education, young people have to choose: The upper track of academic school and colleges for higher vocational education prepare for university entrance. Students who want to enter the labour market early have to continue in a one-year preparatory class (‘Polytechnikum’) before starting apprenticeship training. Furthermore, there is a three-year school-based track for vocational education. Only the upper cycle of academic secondary school does not include vocational education. This means, all students other than those who plan to enter the upper cycle of academic schools are confronted with occupational choices.

3.3 Mixed methods longitudinal research (MMLR)

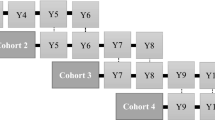

Our mixed methods design can be described as fully longitudinal, equal number, sequential (Vogl 2023). Mixed method research is characterized by a combination of “different sources of data and quantitative and qualitative analytical procedures with the intention to engage multiple perspectives in order to more fully understand complex social phenomenon” (Creamer 2022, p. 7). In exploratory (sequential) designs, qualitative inquiry is followed by quantitative methods (Creswell 2014). In our case, exploratory qualitative interviews were followed by standardised surveys. The panel consists of an equal number of annual interviews in both strands but due to the sequential order—in which the quantitative instruments build on qualitative results—the first qualitative wave started one year ahead of the quantitative and thus the quantitative panel finished one year after the qualitative interviews. Samples for both strands were independent but from the same population (in the respective year of the first interview). Comparisons of results from qualitative and quantitative strands can lead to contradiction (cross-sectionally and/or longitudinally) as well as complementarity. Both can initiate new research questions.

Within this design, we explore patterns of transition and develop a typology of patterns in time for the educational and occupational orientation process of young people at the school-to-work transition, using a grounded theory approach (Kogler et al. 2023b). We used the typology to inform and complement Latent Transition Analysis (LTA) of the survey data. With LTA, we identified 11 patterns of aspirations with important differences depending on social background (Valls et al. 2022). The qualitative results helped us decide which variables to include in the model, how many classes should be specified, and how they could be interpreted. Social background and other demographic variables could not be sufficiently considered in the qualitative strand because of the non-probabilistic and small subsample. Thus, we used quantitative results to triangulate, complement, and expand qualitative findings. To present MMR results, we use a joint display (Guetterman et al. 2015; Bustamante 2019) to facilitate integration by bringing different data types together in one matrix. In the next section, we present the qualitative typology and add statistical results to extend these findings with information on socio-demographic specificities of the types identified.

3.4 Qualitative panel interviews

The first wave of qualitative interviews took place in school settings in spring 2017Footnote 1, and the second and third waves followed in out-of-school settings in winter 2017–2018Footnote 2 and early 2019Footnote 3. In all waves, interviews started with an open narrative part followed by ad hoc questions on the narration, a semi-structured part with a network graph and a short sociodemographic questionnaire. The opening question in Wave 1 was aimed at prompting a narrative on life history, and from Wave 2 onwards, the first question pertained to events since the last interview encounter.

Recruiting participants, we adopted a multi-level most-different-cases approach, selecting five schools from districts in Vienna with strong differences in terms of socioeconomic composition. Thus, after headteacher, class teachers, guardians and finally the adolescents themselves had to consent to conducting the study in a particular school and individual adolescents participating. In the first wave, 107 participants (67 boys and 40 girls) were interviewed. About three-quarters of them had been born in Austria, approximately 20% in another European country, and 10% outside Europe. In the second wave, 48 young people (29 boys, 18 girls, and one person who identified as nonbinary) participated. Eighty percent had been born in Austria. Wave 3 consists of 27 interviews with one participant not participating in Wave 2. Thus 26 young adults (10 boys, 15 girls, and one person identified as nonbinary) participated in all three waves of data collection. Of all Wave 3 respondents, 73% were born in Austria and 46% had both parents born in Austria. Despite the drop-outs, the sociodemographic background of the sample remained comparable (Vogl and Zartler 2021; Wöhrer et al. 2023).

From the 26 cases participating in all three waves, we theoretically sampled 14 cases in an iterative process until theoretical saturation was accomplished: initial analysis of a limited number of cases led to selecting further cases following the idea of constant comparisons. The logic of qualitative longitudinal analysis involves working across cases, themes and time to discern their complex intersections. Within this framework, we combine a thematic, diachronic analysis with constant comparison and coding paradigm from Grounded Theory Methodology (Flick 2018). Thus, we thematically coded content to allow for a comparison between waves and cases. Relating description, arguments and narrations across waves led to a process orientation and helped revealing how and why individual lives unfold (Neale 2021). Within the Grounded Theory framework, we developed a causal understanding and a typology of patterns in time by contrasting cases and putting results on a more abstract theoretical level. Typologies are the result of a grouping process. After individual case reconstructions, dimensions for comparison were identified, cases were grouped to (ideal) types such that they are as homogeneous as possible within one type and as heterogeneous as possible across types (Kluge 2000).

Qualitative longitudinal researchers aim for an understanding of personal life trajectories as they unfold and they strive to understand the dynamics between context and subjectivity, as well as the intersection of biography, history, and society, particularly in times of transitions (McLeod and Thomson 2009; Neale et al. 2012; Shirani and Henwood 2010). Panel studies involve accumulating the retrospective and prospective views for the same individuals at several points in time (Kraus 2000). Participants tell, in hindsight, how they perceived transitions or phases, but do so from their current point of view; and their narratives contain stories about how their future could or should be—in foresight (Thomson and Holland 2003). By analyzing the interplay of hindsight and foresight across time, researchers gain a stronger process orientation.

3.5 Panel survey data

The panel survey data was collected annually from 2018 onwardsFootnote 4. The population for the study were all adolescents attending their final year (8th grade) in the general track of lower secondary schools in Vienna in the winter term 2017–2018. A multi-stage recruitment strategy via schools was used. In the first wave, all Neue Mittelschulen (NMS) in Vienna were invited to participate and further to gain consent from parents and students themselves. The cooperation rate was 75% of the schools (117 in total) with 3078 young people who had started and 2854 who completed the survey (of about 8000 in total) (Wöhrer et al. 2023). In the subsequent waves, 805 adolescents participated in wave 2 and 725 in wave 3; 1000 students participated in at least 2 waves of the panel. For dealing with panel attrition and missing data, we used full information maximum likelihood (FIML), and the final sample analysed included 2545 adolescents. Students were only eliminated from the analysis if they were missing on all observed variables used in the analysis. FIML is robust for missing at random data with the inclusion of missing-data-relevant variables in the models.

We examined young people’s aspirations using latent transition analysis (LTA) to explore the development of aspirations over three years. This method is a type of latent Markov Model (Abarda et al. 2020) and it is also an extension of the Latent Class Analysis which identifies unobservable groups within a sample using observed variables (Collins and Lanza 2010).

The variables for the statistical model are:

-

Educational aspirations. Respondents were asked in every wave which highest educational degree they would like to obtain.

-

Occupational aspirations. The desired occupation was recorded in an open format. The responses were classified using the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI) from 2008 (Ganzeboom et al. 1992) in each wave of the panel.

-

Gender. Male or female. There was a ‘diverse’ option, but we did not include the category in the analysis because of the small number.

-

Parents’ Educational Level. This variable captured the highest parental educational level: compulsory education or no education, secondary education or higher education.

-

Migration background. This variable included non-migrant background, generation 1 (not born in Austria), generation 2 (parents not born in Austria), and generation 2.5 (one parent not born in Austria).

-

School grades. Students were asked to report their school grades in mathematics and English in the last report card. The possible answers were 1 (excellent) to 7 (fail).

In the statistical analysis, using LTA (Collins and Lanza 2010), we integrated the occupational and educational aspirations in order to identify groups of individuals with different aspirations and to see how that aspirations change over time (for further details, Valls et al. 2022). Using LTA, a latent class analysis was estimated at each time point and the probability of transitioning from one class to another was also estimated. The quantitative analysis resulted in an optimal solution of a five-class model in each wave (see Table 1): (1) High aspirations: aspiration to obtain a university degree and an occupation with an ISEI of more than 71; (2) Medium-High aspirations: aspiration to obtain a Matura certificate and an occupation with an ISEI between 57 and 70; (3) Low aspirations: aspiration to obtain a diploma of apprenticeship or a compulsory school leaving certificate and an occupation with an ISEI of 40 or less; (4) Medium-Low occupational aspirations and educational indecision: aspiration to an occupation with an ISEI between 41 and 56 and undefined desired education; and (5) Indecision: students who do not know which degree they would like to achieve and do not state a desired occupation.

4 Results: Patterns in time of orientation processes

We focused on orientation processes as dynamic intentions and hopes, not as single steps or decisions, among adolescents at lower secondary schools in Vienna. The longitudinal perspective offers insights into the temporal dimension of the aspects and consequences of change and their interplay. In the qualitative analysis, based on the analysis of 14 cases over three waves, we identify four types of orientation processes in our interview material: “determined”, “resigning”, “step-by-step aspiring” and “drifting”. These patterns in time for educational and occupational orientations have varying degrees of determination and concreteness, change and stability. Comparing these types, we identify two basic patterns in time: stable process or continuation over time as well as spiral shaped processes (Kogler et al. 2023a). Both determined and drifting young people represent a stable pattern: Whereas the first type steadily works towards educational and occupational goals, the second consistently lacks a clear aim. Determined and drifting adolescents share consistency in their occupational and educational trajectories: consistently clear vs. consistently vague. The spiral pattern describes the types resigning and step-by-step aspiring. Their orientation process can be described as a spiral regarding concreteness of aspirations but in opposite directions: step-by-step aspiring’s orientation process starts wide and narrows over time—vague ideas and first steps towards education and employment helping to define future steps. In contrast, resigning young people start with a rather clear idea, but cannot achieve their goals and segue into disorientation and resignation.

The longitudinal statistical results for the three waves of the panel—including the covariates—showed eleven aspirational patterns (Valls et al. 2022). The classes of patterns identified in the statistical analysis were very similar to the qualitative typology but there were more classes than qualitative types—given the different sample sizes, and the way to create ideal types, this is not surprising. In order to compare and integrate patterns detected in the qualitative and the statistical analyses, we clustered the classes into six groups: (1) determined—with a distinction between (a) high, (b) medium and (c) low aspirations-, (2) resigning, (3) step-by-step aspiring and (4) drifting.

In terms of numbers, the stability patterns—determined and drifting—are the most frequent in the statistical analysis (73.8%): these young people have either consistently clear or consistently vague aspirations over three yearsFootnote 5. However, the statistical analysis revealed some additional differences in the determined-group, namely between different levels of stable aspirations: stable high aspirations (27.8%), stable medium-high aspirations (8.4%), and stable low aspirations (23%). Furthermore, the pattern drifting (19.1%) consists of students without concrete occupational or educational aspirations or medium-low occupational aspirations and educational indecision, or their orientation process has other complex patterns. Regarding those with changing aspirations, we could identify resigning (11.6%) students with decreasing aspirations over time or aspirations changing to indecision over time. Step-by-step aspiring (10.2%) refers to patterns of either increasing aspirations over time or changes from indecision to aspirations.

In sum, the statistical results showed important differences in the development of aspirations according to the sociodemographic profile of young people, also when controlling for school grades. Firstly, English and Mathematics grades were significant for some aspirational patterns. The worse the Maths and English grades, the lower the likelihood of falling into the determined, stable high aspirations group and the higher the likelihood of being determined with stable low aspirations. Secondly, regarding the impact of the parental educational level, the results showed that students whose parents have compulsory education or secondary education were more likely to have stable low aspirations or changing aspirations (i.e. resigning and step-by-step). In contrast, young people with parents with higher education were more likely to show stable aspiration patterns, determined high but also drifting aspirations. Furthermore, young people whose parents have secondary education were more likely to be determined with stable medium aspirations compared to those whose parents have higher education. Thirdly, young people from migration generation 1, 2, and 2.5 were more likely to be determined with high stable aspirations than non-migrant respondents, and less likely to have low stable aspirations. Moreover, generation 2 and 2.5 participants were more likely to be in the drifting group and less likely to be in the step-by-step aspiring group. Furthermore, generation 1 was less likely to be in the resigning group in comparison to those without migration background. Therefore, young people without migration background are more likely to be “determined” with low stable aspirations and changing patterns.

We will now characterize these types of orientation patterns and then compare them based on relevant dimensions that distinguish the types. Table 2 combines all qualitative and quantitative results in a joint display.

Determined

Determined young people have clear ideas of what they want to achieve and they take necessary steps on their own. They see many options for themselves and believe they can achieve their goals. Self-confidence and determination go hand in hand with them taking action and making their way independently. Although friendships change, they are intense and friends are either determined themselves or support the aspirations. Also, the family supports these determined young people both emotionally and instrumentally but the family’s (occupational and educational) expectations of the adolescents are rather vague. When parents have a higher educational degree, their children’s aspirations tend to be higher. Also, migration background leads to higher aspirations in this group, so do better grades in Math and English. In other words, those with good grades, migration background and higher educated parents are more likely to have high stable aspirations. The determined type is the biggest group with almost 60% of respondents.

Drifting

With consistently changing and vague ideas of educational and occupational aspirations, young people with a drifting orientation process struggle in several respects: these young people have only a vague idea of options, are overwhelmed with decisions, and increasingly insecure and have self-doubts. This also leads to a certain stagnation—no strategies to overcome this drifting pattern could be detected. In addition, the family is not helping, they do not offer instrumental or emotional support. Furthermore, friendships tend to be loose and changing. Thus, friends also do not back the orientation process. Adolescents with lower educated parents (compared to parents with higher formal education) and lower Math grades are less likely to have drifting orientation process. In contrast, young people of migration generation 2 and 2.5 are more likely to fall into this pattern (in comparison to young people without migration background). Adolescents with a drifting orientation process account for almost 20% of respondents—in other words, a considerable number of adolescents does not know what to do and need advice, the family and friends might not (be able to) provide.

Resigning

The orientation process of the resigning group is characterized by a downward movement of aspiration levels or increasing vagueness: both educational and occupational aspirations change, also because strategies or choices were not successful. Options vanish and the space of possibilities shrinks. This goes hand in hand with decreasing self-esteem and resignation. In contrast, the expectations of the family are high and persistent which puts these young people under pressure but leaves them without instrumental support. Friendships are strong and stable but friends are not helping them in their orientation process. Parents with lower educational levels increase the probability of falling into this pattern of change (in comparison with parents with higher education). One in ten of our survey respondents showed this orientation pattern.

Step-by-step aspiring

Changing but with an upward trend in aspiration levels and growing concreteness of plans describes the step-by-step aspiring pattern. Although the space of possibilities remains vague it grows in size, more options become thinkable. Although options and decisions seemed overwhelming initially, these adolescents show resilience, they adapt flexibly and make decisions. This leads to growing self-esteem. The emotional support from the family with generally high but vague expectations seems important. Again, parents with lower education levels increase the likelihood to fall in this pattern (compared to parents with higher education). Second generation migrants are rare in this group, they were more likely to show the drifting pattern (compared to non-migrant respondents). About 10% of respondents can be classified as step-by-step aspiring.

Contrasting these types, we found important differences between young people and their orientation processes. One dimension in the qualitative results was the subjective space of possibilities as the perceived options, the thinkable and unthinkable that guides young people’s decisions and goals. The space of possibilities is particularly relevant in the decision-making process and in school-to-work transitions. It shapes educational and occupational orientations and serves as a framework for them. This perception of options changes with experiences, also the perceived failure and success regarding one’s own goals, and interactions with others (family and friends as well as teachers or instructorsFootnote 6), and thus, it evolves over time. It not only mirrors “real” options but also includes the perception thereof. The behavioral strategies in the transitional phase and the self-perception are closely intertwined. Determined young people are proactive and have a consistently large space of possibilities with clear objectives and high levels of self-efficacy and increasing self-esteem. In contrast, for drifting adolescents, the space of possibilities remains consistently vague and goes hand in hand with low self-esteem and insecurities. These adolescents remain passive and lack a clear strategy for their transition. A shrinking space of possibilities, decreasing self-esteem and resignation characterize the resigning type. Low self-efficacy which leads to delayed actions, procrastination, and pragmatic decisions rather than choices with conviction. In contrast, step-by-step aspiring adolescents are resilient and adaptable with a growing subjective space of possibilities and increasing self-esteem.

The social context, particularly the family, plays an important role for the orientation process but in different ways: expectations and instrumental and emotional support are important factors for shaping the orientation process. High but intangible expectations of the family and little immediate support put resigning under pressure. Step-by-step aspirings’ families also have high but intangible expectations, yet, they provide emotional (and unconditional) support; although friendships are important to young people, they do not play a clear role in the orientation process of either step-by-step aspiring or drifting young people. For determined adolescents, general, unconditional support from their family stabilizes their orientation process; their friendships change but their friends are supportive of their aspirations and equally determined. Drifting young people are disoriented; they lack support, and family members do not guide them. Their friends are equally disoriented which is counterproductive for the orientation processes.

5 Conclusion and discussion

In this exploratory longitudinal mixed methods research, we integrated quantitative results on patterns of time for sub-groups and analyses of qualitative interviews to untangle the multidimensional phenomenon of educational and occupational orientations over time. Our results contribute to the debate on the development of aspirations in the transitional phase after finishing compulsory schooling. They provide insights into the role of academic performance and sociodemographic characteristics of young people for explaining the different patterns of orientation processes but also patterns behind different types of developments of educational and occupational aspirations. With this innovative integration of qualitative and quantitative interview results, we move towards unpacking the black box of young people’s orientations during school-to-work transitions (Nießen et al. 2022; Schels and Abraham 2021; Tomasik et al. 2009).

Like other longitudinal projects on transitions (Du Bois-Reymond et al. 2001; Furlong and Biggart 1999; Hegna 2014), ‘Pathways to the Future’ showed that a number of young people change their educational aspirations during the three-year period after compulsory schooling (Valls et al. 2022). However, a surprisingly high amount of young people has stable aspirations. Sixty percent of students had stable aspirations over this three-year period. We found a smaller number of students who had changing aspirations (about 20%) or patterns of undecidedness (drifting; about 20%).

Our results show how the orientation process goes hand in hand with the development of self-perception. Parents play an important role—with their support and expectations as well as their educational level. We also showed that grades play a role in the orientation process—in a predictable way for stable aspirations but less obvious for drifting or changing patterns. Even after controlling for grades, the results show important differences in orientation patterns according to sociodemographic variables. On the one hand, migration background and a high level of parental education were associated with different levels of stable aspirations. One possible explanation for this is that migrants anticipate discrimination at the lower occupational level that they can avoid with higher education (Tjaden 2017) or immigrant optimism (Fernández-Reino 2016; Salikutluk 2016). Moreover, non-migrant students and low parental education were related to the likelihood of being in the determined stable low pattern. On the other hand, the patterns of change were more likely among non-migrant young people and with those whose parents have compulsory education or less. Therefore, the lower the educational background, the more likely young people are to change aspirations after finishing NMS, both downwards—as also pointed out by Jackson et al. (2012)—and upwards.

Our study results illustrate how mixed methods longitudinal research can yield a more holistic, temporal and nuanced understanding of structure and agency. With mixed-methods longitudinal studies, researchers have a very powerful methodology for exploring and explaining change and continuities. It is also a very demanding methodology in terms of resources and reflection, and the longitudinal character holds challenges that go beyond or magnify those of cross-sectional research. We demonstrated the value of using a longitudinal approach to obtain young people’s perspectives in order to understand the interplay of their (self‑)perceptions, spaces of possibilities and the varying scopes of behavioral strategies, support of family and friends and agency, but also school performance and socio-demographic background over time. Qualitative material shows a more nuanced orientation process and more holistic in terms of dimensions. Quantitative data has the strengths of confirming the patterns and extending qualitative results by bringing socio-demographic factors into the typology that could not be considered reliably in the qualitative analysis due to a small sample size.

With the qualitative analysis we could determine patterns in time of developing aspirations and their relation to other factors like family and friends. However, we could not determine frequency of occurrence of these patterns in the population. The credibility and validity of the qualitative typology is supported by the exploratory statistical analysis which identified the same patterns—although with different nuance. The advantage of the statistical results is a frequency description on the one hand but a confirmation and extension of the qualitative results on the other. Statistical analyses were complementary in this respect. Discrepancy between qualitative and quantitative becomes obvious too: qualitative data shows more insecurities, self-doubts and self-confidence than quantitative patterns could. Furthermore, the mechanisms behind reproduction of social inequality become more tangible, i.e. in the relevance of different types of support but also a qualification of family members’ expectations rather than the mere level of education obviously determine the development of aspirations. In addition, the role and characteristics of friendships and peers differ between young people with different patterns of educational and occupational orientations.

Qualitative data also brings agency to the light—agency is required to navigate the transitional process but remains hidden in variable-based approaches. Navigating institutionalized transitions refers to the need to choose certain points in the biography to uncover the interplay of structures (especially institutional frames and socioeconomic variables) and agency (Walther et al. 2015). As we have shown in our analysis (Kogler et al. 2022), agency is an evolving process (Bryant and Ellard 2015) and is reflected in increasing self-awareness and higher levels of control. Young people prove agency by imagining a future (Ravn 2019; Carabelli and Lyon 2016). However, often young people do not have concrete plans for their whole life by the end of obligatory schooling. We also showed that agency can be developed in different ways during the transitional phase and there are varied ways of dealing with this navigation process.

Despite individuality of biographies, our results show distinct transition patterns for young people in Vienna, Austria. Most likely, for many of our respondents’ aspirations have been pre-adjusted during NMS and therefore there is no further ‘need’ for (major) adjustments. This could be due to the strongly tracked educational and VET system. However, for some young people, decisions at around 15 years are too early in the life course because they have not yet formed aspirations that could guide them through the transitional phase. Nonetheless the negative consequences of disorientation for self-perception and agency became obvious. More institutional guidance and later decision points could be beneficial for some adolescents and avoid inequality.

Notes

Flecker et al. (2017).

Vogl and Zartler (2018).

Wöhrer et al. (2019).

However, some re-orientations could be overlooked if they are within a certain range of ISEI scores or the educational aspiration changes horizontally rather than vertically.

Teachers were only mentioned in a limited number of qualitative interviews and mostly in cases where teachers compensated for lacking parental guidance or support (Zartler et al. 2020).

References

Abarda, Abdallah, Mohamed Dakkon, Mourad Azhari, Abdellah Zaaloul, and Mostafa Khabouze. 2020. Latent transition analysis (LTA): a method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. Procedia Computer Science 170:1116–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2020.03.059.

Astleithner, Franz, Susanne Vogl, and Michael Parzer. 2021. Zwischen Wunsch und Wirklichkeit: Zum Zusammenhang von sozialer Herkunft, Migration und Bildungsaspirationen. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-021-00442-3.

Barrett, Timothy. 2015. Storying Bourdieu. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915621399.

Baumann, Zygmunt. 1998. Consumerism and the new poor. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Boudon, Raymond. 1974. Education, opportunity, and social inequality: changing prospects in western society. New York: Wiley.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1983. The field of cultural production, or: the economic world reversed. Poetics 12(4):311–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-422X(83)90012-8.

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1977. Reproduction in education, society and culture. Theory, culture & society. London: SAGE.

Bryant, Joanne, and Jeanne Ellard. 2015. Hope as a form of agency in the future thinking of disenfranchised young people. Journal of Youth Studies 18(4):485–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.992310.

Brzinsky-Fay, Christian. 2014. The measurement of school-to-work transitions as processes. European Societies 16(2):213–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2013.821620.

Busse, Susann. 2010. Bildungsorientierungen Jugendlicher in Familie und Schule. Die Bedeutung der Sekundarschule als Bildungsort. Wiesbaden: VS. Zugl.: Diss.

Bustamante, Carolina. 2019. TPACK and teachers of Spanish: development of a theory-based joint display in a mixed methods research case study. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 13(2):163–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689817712119.

Carabelli, Giulia, and Dawn Lyon. 2016. Young people’s orientations to the future: navigating the present and imagining the future. Journal of Youth Studies 19(8):1110–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1145641.

Collins, Linda M., and Stephanie T. Lanza. 2010. Latent class and latent transition analysis. With applications in the social behavioral, and health sciences. Hoboken: Wiley.

Creamer, Elizabeth G. 2022. Advancing grounded theory with mixed methods. London, New York: Routledge.

Creswell, John W. 2014. Research design. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Diehl, Claudia, Christian Hunkler, and Cornelia Kristen (eds.). 2016. Ethnische Ungleichheiten im Bildungsverlauf. Mechanismen, Befunde, Debatten. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH.

Dietrich, Julia, and Bärbel Kracke. 2009. Career-specific parental behaviors in adolescents’ development. Journal of Vocational Behavior 75(2):109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.03.005.

Du Bois-Reymond, Manuela, Wim Plug, Yolanda Te Poel, and Janita Ravesloot. 2001. ‘And then decide what to do next…’ Young people’s educational and labour trajectories: A longitudinal study from the Netherlands. YOUNG 9(2):33–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/110330880100900203.

Evans, Karen. 2002. Taking control of their lives? Agency in young adult transitions in England and the New Germany. Journal of Youth Studies 5(3):245–269.

Feliciano, Cynthia, and Yader R. Lanuza. 2017. An immigrant paradox? Contextual attainment and Intergenerational educational mobility. American Sociological Review 82(1):211–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416684777.

Fernández-Reino, Mariña. 2016. Immigrant optimism or anticipated discrimination? Explaining the first educational transition of ethnic minorities in England. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 46:141–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2016.08.007.

Flecker, Jörg, Andrea Jesser, and Veronika Wöhrer. 2017. Pathways to the Future. A longitudinal study about the socialization of young people in Vienna. Qualitative Panel, Wave 1. Department of Sociology, University of Vienna. Research project.

Flecker, Jörg, Susanne Vogl, and Franz Astleithner. 2018. Pathways to the Future. A longitudinal study about the socialization of young people in Vienna. Quantitative Panel, Wave1. Department of Sociology, University of Vienna. Research project.

Flick, Uwe. 2018. Doing grounded theory. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Furlong, Andy, and Andy Biggart. 1999. Framing ‘Choices’: a longitudinal study of occupational aspirations among 13- to 16-year-olds. Journal of Education and Work 12(1):21–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363908990120102.

Ganzeboom, Harry B., Paul M. de Graaf, and Donald J. Treiman. 1992. A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social science research 21(1):1–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-089X(92)90017-B.

Gaupp, Nora. 2013. School-to-work transitions—findings from quantitative and qualitative approaches in youth transition research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 14(2).

Gottfredson, Linda S. 1981. Circumscription and compromise: a developmental theory of occupational aspirations. Journal of Counseling Psychology 28(6):545–579. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.28.6.545.

Guetterman, Timothy C., John W. Creswell, and Udo Kuckartz. 2015. Using joint displays and MAXQDA software to represent the results of mixed methods research. In Use of visual displays in research and testing, coding, interpreting, and reporting data, ed. Matthew T. McCrudden, Gregory Schraw, and Chad Buckendahl, 145–176. IAP.

Gutman, Leslie M., and Ingrid Schoon. 2012. Correlates and consequences of uncertainty in career aspirations: gender differences among adolescents in england. Journal of Vocational Behavior 80(3):608–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.02.002.

Heckhausen, Jutta, and Marlis Buchmann. 2019. A multi-disciplinary model of life-course canalization and agency. Advances in Life Course Research 41:100246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2018.09.002.

Hegna, Kristinn. 2014. Changing educational aspirations in the choice of and transition to post-compulsory schooling—a three-wave longitudinal study of Oslo youth. Journal of Youth Studies 17(5):592–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.853870.

Hermes, Michael. 2017. Bildungsorientierungen im Erfahrungsraum Familie. Rekonstruktionen an der Schnittstelle zwischen qualitativer Bildungs‑, Familien- und Übergangsforschung. Leverkusen, Opladen: Budrich.

Jackson, Michelle, Jan O. Jonsson, and Frida Rudolphi. 2012. Ethnic inequality in choice-driven education systems. Sociology of Education 85(2):158–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040711427311.

Kluge, Susann. 2000. Empirically grounded construction of types and Typologies in qualitative social research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research Qualitative Research: National, Disciplinary, Methodical and Empirical Examples. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.1.1124.

Kogler, Raphaela, Susanne Vogl, and Franz Astleithner. 2022. Plans, hopes, dreams and evolving agency: case histories of young people navigating transitions. Journal of Youth Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2022.2156778.

Kogler, Raphaela, Susanne Vogl, and Franz Astleithner. 2023a. Transitions, choices and patterns in time: Young people’s educational and occupational orientation. Journal of Education and Work. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2023.2167954.

Kogler, Raphaela, Susanne Vogl, and Franz Astleithner. 2023b. Übergänge, Entscheidungen und Verlaufsmuster: Bildungs- und Berufsorientierungen Jugendlicher. In Junge Menschen gehen ihren Weg. Längsschnittanalysen über Jugendliche nach der Neuen Mittelschule, ed. Jörg Flecker, Brigitte Schels, and Veronika Wöhrer, 59–78. V&R unipress.

Kraus, Wolfgang. 2000. Making identity talk. On qualitative methods in a longitudinal study. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 1(2):15. https://doi.org/10.17169/FQS-1.2.1084.

Mataloni, Barbara, Camilo Molina Xaca, and Christoph Reinprecht. 2020. Pathways to the Future. A longitudinal study about the socialization of young people in Vienna. Quantitative Panel, Wave3. Department of Sociology, University of Vienna. Research project.

McLeod, Julie, and Rachel Thomson. 2009. Researching social change. Qualitative approaches. Los Angeles, Calif: SAGE.

Möser, Sara. 2022. Naïve or persistent optimism? The changing vocational aspirations of children of immigrants at the transition from school to work. Swiss Journal of Sociology 48(2):255–284. https://doi.org/10.2478/sjs-2022-0015.

Neale, Bren. 2021. Qualitative longitudinal research. Research methods. London: Bloomsbury academic.

Neale, B., K. Henwood, and J. Holland. 2012. Researching lives through time. An introduction to the Timescapes approach. qualitative research 12(1):4–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111426229.

Nießen, Désirée, Alexandra Wicht, Ingrid Schoon, and Clemens M. Lechner. 2022. “you can’t always get what you want”: prevalence, magnitude, and predictors of the aspiration-attainment gap after the school-to-work transition. Contemporary Educational Psychology 71:102091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2022.102091.

Ravn, Signe. 2019. Imagining futures, imagining selves: a narrative approach to ‘risk’ in young men’s lives. Current Sociology 67(7):1039–1055. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392119857453.

Reinprecht, Christoph, Barbara Mataloni, and Camilo Molina Xaca. 2019. Pathways to the Future. A longitudinal study about the socialization of young people in Vienna. Quantitative Panel, Wave2. Department of Sociology, University of Vienna. Research project.

Salikutluk, Zerrin. 2016. Why do immigrant students aim high? Explaining the aspiration-achievement paradox of immigrants in Germany. European Sociological Review 32(5):581–592. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcw004.

Schels, Brigitte, and Martin Abraham. 2021. Adaptation to the market? Status differences between target occupations in the application process and realized training occupation of German adolescents. Journal of Vocational Education & Training. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2021.1955403.

Scherger, Simone, and Mike Savage. 2010. Cultural transmission, educational attainment and social mobility. The Sociological Review 58(3):406–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2010.01927.x.

Schoon, Ingrid, and Mark Lyons-Amos. 2016. Diverse pathways in becoming an adult: the role of structure, agency and context. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 46:11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2016.02.008.

Shirani, Fiona, and Karen Henwood. 2010. Continuity and change in a qualitative longitudinal study of fatherhood. Relevance without responsibility. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 14(1):17–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645571003690876.

Stocké, Volker. 2005a. Idealistische Bildungsaspiration. Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen

Stocké, Volker. 2005b. Realistische Bildungsaspiration. Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen

Thomson, Rachel, and Janet Holland. 2003. Hindsight, foresight and insight. The challenges of longitudinal qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 6(3):233–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000091833.

Tikkanen, Jenni, Piotr Bledowski, and Joanna Felczak. 2015. Education systems as transition spaces. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 28(3):297–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.987853.

Tjaden, Jasper Dag. 2017. Migrant background and access to vocational education in Germany: self-selection, discrimination, or both? Zeitschrift Für Soziologie. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2017-1007.

Tomasik, Martin J., Sam Hardy, Claudia M. Haase, and Jutta Heckhausen. 2009. Adaptive adjustment of vocational aspirations among German youths during the transition from school to work. Journal of Vocational Behavior 74(1):38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.10.003.

Valls, Ona, Franz Astleithner, Brigitte Schels, Susanne Vogl, and Raphaela Kogler. 2022. Educational and occupational aspirations: a longitudinal study of Vienna youth. Social Inclusion 10(2):226–239. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v10i2.5105.

Vogl, Susanne. 2023. Mixed methods longitudinal research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.4012.

Vogl, Susanne, and Ulrike Zartler. 2018. Pathways to the Future. A longitudinal study about the socialization of young people in Vienna. Qualitative Panel, Wave 2. Department of Sociology, University of Vienna. Research project.

Vogl, Susanne, and Ulrike Zartler. 2021. Interviewing adolescents through time: balancing continuity and flexibility in a qualitative longitudinal study. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 12(1):83–97. https://doi.org/10.1332/175795920X15986464938219.

Walther, Andreas, and Wim Plug. 2006. Transitions from school to work in Europe: destandardization and policy trends. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2006(113):77–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.170.

Walther, Andreas, Annegret Warth, Mirjana Ule, and Manuela Du Bois-Reymond. 2015. ‘Me, my education and I’: constellations of decision-making in young people’s educational trajectories. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 28(3):349–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.987850.

Wicht, Alexandra, and Wolfgang Ludwig-Mayerhofer. 2014. The impact of neighborhoods and schools on young people’s occupational aspirations. Journal of Vocational Behavior 85(3):298–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.08.006.

Willis, Paul E. 1977. Learning to labor: how working class kids get working class jobs. New York: Columbia University Press.

Winterton, Mandy T., and Sarah Irwin. 2012. Teenage expectations of going to university: the ebb and flow of influences from 14 to 18. Journal of Youth Studies 15(7):858–874. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2012.683407.

Wöhrer, Veronika, Yuri Kazepov, and Christoph Reinprecht. 2019. Pathways to the Future. A longitudinal study about the socialization of young people in Vienna. Qualitative Panel, Wave 3. Department of Sociology, University of Vienna. Research project.

Wöhrer, Veronika, Susanne Vogl, Brigitte Schels, Paul Malschinger, Barbara Mataloni, and Franz Astleithner. 2023. Methodische Grundlagen und Forschungsdesign der Panelstudie. In Junge Menschen gehen ihren Weg. Längsschnittanalysen über Jugendliche nach der Neuen Mittelschule, ed. Jörg Flecker, Brigitte Schels, and Veronika Wöhrer, 29–56. V&R unipress.

Zartler, Ulrike, Susanne Vogl, and Veronika Wöhrer. 2020. Familien als Ressource? Perspektiven Jugendlicher auf die Rollen ihrer Eltern bei Bildungs- und Berufsentscheidungen. In Wege in die Zukunft. Lebenssituation Jugendlicher am Ende der Neuen Mittelschule, ed. Jörg Flecker, Veronika Wöhrer, and Irene Rieder, 147–169. Göttingen: V&R unipress.

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by the Austrian National Bank (OeNB) under grant agreement number 18283 “When Dreams (Do Not) Come True” (PI Susanne Vogl). We would like to thank the Department of Sociology at the University of Vienna and the members of the steering group of the project “Pathways to the Future” for their support.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S. Vogl, O. Valls, R. Kogler and F. Astleithner declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vogl, S., Valls, O., Kogler, R. et al. The dreams they are a-changin’: Mixed-methods longitudinal research on young people’s patterns of orientation. Österreich Z Soziol 48, 309–331 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-023-00540-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-023-00540-4